Imagine if people from the past left no clue as to how they lived. How would we able to piece together such aspects of their life as their eating habits, their customs, and their belief systems? How would we be able to understand the joys and struggles they went through? How would we learn from them? When you visit a temple along the Shikoku pilgrimage route what do you look at? Do you try to find traces of people who have visited there in the past and when you find them are you curious to find out when, why, or how this was left there by those people?

One of the earliest “marks” left by pilgrims is graffiti written on some temple walls during the 16th century. It sounds no different from people today carving their names in trees, benches or other objects. However, this offers solid proof that people were making the pilgrimage more than three hundred years ago. Other people from the past hundred years or so have pasted paper or wooden osamefuda or senjafuda (name-slips) all over the pillars or walls of the temple buildings, and some have left paraphernalia such as crutches, leg braces, or wagons at temples because they been cured of an illness or disability and no longer needed them. Personally, I like to collect old materials about the Shikoku pilgrimage, especially photographs with pilgrims looking directly toward the camera. Who were they? What is their story? Why did they decide to embark on the lengthy and arduous Shikoku pilgrimage?

Self-mutilation seems to be a part of Buddhism with many examples seen in China of people burning or biting their fingers off as an offering to Buddha as a sign of repentance, or to support a special vow. In Japan, there are examples in Japanese tales, plays, the yakuza (mafia) and the world of courtesans to show one’s love or loyalty. Even today, children make promises by connecting their pinkies and saying, “yubi kiri genman, uso wo tsuitara, hari senbon nomasu, yubi kitta.” If you lie, I will punch you ten thousand times, make you drink 1000 needles and cut off your finger. Unfortunately, it is unknown when, why, or how this bizarre action was performed by pilgrims in Shikoku during the early 20th century.

There are three examples in two short books published in 1916 and 1925 about Temple 19, Tatsue-ji:

- In May 1909, Dai Fujiwara, age 22, from Ehime prefecture was sick and so with a sincere heart he prayed devotedly to the gods and completed the Shikoku pilgrimage. He received a blessing from the main deity and completely recovered. He was so happy that he cut off his finger and left it at Tatsue-ji.

- On April 24th, 1915, Hyakutaro Okuno from Okayama prefecture became sick. He believed in Jizō with all of his heart and received a blessing. He cut off the end of his little finger and as a sign of the fulfilment of his prayers left it at Tatsue-ji.

- Mine Ishihara, age 24, from Fukuoka prefecture had suffered from epilepsy from a young age and his only solace was to believe in Jizō and pray for a cure. One night, the figure of Jizō appeared above her pillow and showed her the cure. She was so happy that on June 3, 1922, she came to Tatsue-ji to worship. The next day, she cut off one finger from her left hand and placed it in front of the gods.

Another example is found in Shikoku Hachjuhachi Fudasho Henroki (四国八十八札所遍路記) by Sakae Nishibata (pub 1964). During the Taisho period (1912-1926) a couple and their disabled daughter, Ai, from Hyogo prefecture came to Shikoku to make the pilgrimage. When they arrived at one of the temples the parents put a vest on Ai with the words Namu Amida Butsu written on it and Ai went to the temple to pray. She put her hands together and said, “Namu Amida Butsu”, but this was the first time ever for her to speak. Her parents were extremely surprised and asked her to repeat other words, which she was able to do so without any problem. The mother, frantic with joy, bit off one finger and gave it to the temple. The author states that the finger, soaked in alcohol, is still there.

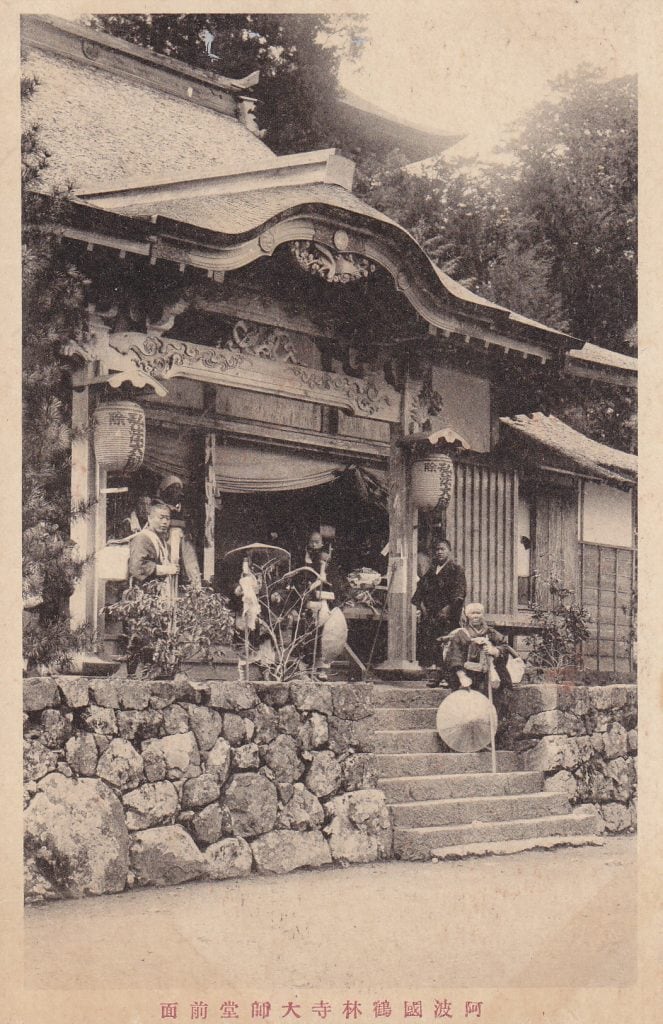

There are also stories of fingers in jars at temples around Shikoku. For example, in the book, Haikai Angya: Ohenrosan (俳諧行脚:お遍路さん), (pub. 1927), the author states that when he visited Temple 70, Motoyamaji he saw a pickled ring finger in a jar hanging by the entrance of the Daishi hall. This apparently belonged to a forty-year pilgrim from Okayama who visited here around 1916 and purposefully cut off his finger with a knife. In Shikoku Reiseki Shashin Daikan (四國靈蹟寫眞大觀) (pub. 1934) there is a photograph of nine clear bottles and five dark bottles at Temple No. 40 Kanjizai-ji. The caption states that the fingers have been given to the temple. The labels above the jars state the sickness from which the pilgrim was cured, for example, blindness, deaf and dumbness, being crippled, epilepsy, uterine cancer, intestinal problems, and mental problems. Unfortunately, there are no written records as to whose fingers they were or when or why they were given.

Presently, such fingers are no longer on display, which is unfortunate because viewing them demonstrates to us the strong degree of devotion that people had a hundred years ago. In recent years, several temples have also removed all the leg braces and crutches etc. used by pilgrims of old. Why? Do temple owners not want modern-day visitors to know about people who came in the past? Are they anxious to sweep away history? While the custom of giving a portion of one’s finger would today be considered grotesque, it is an interesting part of the religious history of the Shikoku pilgrimage that should not be overlooked nor forgotten.

This article was first published in the March 2015 issue of Awa Life.

How about the knitted head coverings that adorn many statues, and the baby bibs and aprons? What do they signify and why are they not removed, since they are not part of the original sculptures?