Dispatches from SabbaticalLand – Part IV

In my latest dispatch about my time in Shikoku, I describe the end of my journey through the Kagawa prefecture, the place of Nirvana, and beyond. Below, you’ll find:

i. the final day – gifts

ii. the day after – mystery

iii. epilogue – reflections

i. the final day

At 5am on my final day, I started out towards the light from the rising sun. I had already reached Temple 88 the day before, but the pilgrimage isn’t finished until you’ve walked over 40 kilometers back to Temple 1. For Henro, Shikoku is a circle.

Pilgrimages come in all different shapes and sizes. The Catholic Camino de Santiago is a line. Jewish Uman, Ukraine is a point [1]. The fact that the Shikoku pilgrimage ends where it begins is perfectly Buddhist and similarly frustrating.

The end of the Camino de Santiago funnels all pilgrims from its eight separate routes into a single corridor. The feelings of accomplishment and joy are tangible: in every direction pilgrims embrace and greet strangers with the familiar “buen camino” heard all along the trail. The streets are crowded with pilgrims, well-wishers and tourists alike. Yellow arrows guide the masses into a grand, open plaza, where they are dwarfed by the towering Santiago de Compostella Cathedral. The Cathedral fills to capacity as it hosts enormous Masses to bless the successive rounds of pilgrims arriving. The newly anointed Camino pilgrim staggers away from the process dazed, but certain they’ve accomplished something.

The Shikoku Pilgrimage ends with about as much fanfare as a trip to the grocery store. Henro can technically start or end at any of the temples, as long as all 88 are visited in order. But the order itself is up for interpretation. With this many options and requirements, it’s no wonder finishing the trek feels anticlimactic.

I’d gradually come to a realization on the last leg of the trip: I wasn’t going to change much about myself at this point. Instead, I tried to honor what I’d learned. I thought back to the first Henro I met, on day one of the pilgrimage. Just hours into my walk, a Ukrainian named Anna approached me at Temple 3. Her face was tan, and her eyes were blue and alive. She spoke perfect English and had the permanent grin of a cult leader.

“Are you just starting out?” she asked.

Relieved to meet someone I could pepper with questions, I dismounted my backpack, and asked if it was so obvious that I’d just begun. In retrospect, I was likely wandering around in circles, searching for the stamp office.

She continued: “I’m just finishing today; it still hasn’t sunk in that it’s over.”

I asked Anna for advice, and generally rushed through what I mistakenly assumed would be regular encounters with English speakers. She told me she’d started early in the season and there was still snow covering Temple 88. She rattled off a list of particulars, including her favorite temples and lodging, and I scribbled notes in my map book.

She continued: “Just remember, no matter how hard it feels at any given time, you’ll get through it. Oh, and of course! You’re going to need plenty of these…”

She rummaged through her bag for a few moments, pulling out a golden wrapped rectangular bar labeled “Calorie Mate.”

“It’s the closest thing you’ll find to energy bars here. You can find them at some convenience stores and vending machines. It’s crucial to have one or two in your pack for emergencies. You won’t always find dinner.”

——————-

And so, on my last day, I purchased 6 boxes of Calorie Mate bars, and filled each with band-aids for blisters, henro stickers, and candies. Protruding from each box was a handwritten osamefuda with my contact details. I had in mind that I would meet some foreign henro, and keep up communications throughout their pilgrimage, just as Anna had done.

Because of the shape of the trail, the first Temple I reconnect with was Temple 3. I set up my base under a shelter in the expansive Temple courtyard to distribute my care packages. But the first new henro I saw was a Japanese retiree. I withheld my gift as I watched him go through the steps at the temple complex. I watched as he dropped his incense case, scattering its contents upon the ground. A gentle drizzle started, and he scrambled over to where I sat, to wrap his newly purchased stamp book in plastic. Clearly flustered, he sat down and caught my eye. I handed over my care package, and strung together a few terms in Japanese. He smiled broadly, bowing in short bursts over the table between us.

He could ask no questions, and I could share no advice. We sat on opposite sides of a momentous thing on which we would have meaningfully different experiences. He couldn’t read my note, much less email me from the route. A few moments of silence later, he launched up and out into the elements. I gave out five of my six of my care packages, wordlessly, to male retired Japanese henro. There weren’t even enough Henro for my gifts. Shikoku’s stubborn insistence on giving you what it wants persisted through to the last day.

The gifts in Shikoku were small, but they usually arrived at just the right time: either when you needed it most, or when you expected it the least. Some were handmade. For example, small pouches from older ladies with fortunes inside. Others were monetary. Once I stood trancelike, several inches away from a vending machine, weighing the many merits and drawbacks of hot versus cold canned coffee. A woman carrying her child swooped in to buy me two sports drinks instead. Many gifts were edible: fruit out of a passing car’s window, or extra portions at restaurants. Back home, gifts are usually big undertakings – you set out to purchase a fleet of presents for Christmas, or you contemplate whether the dollar value of your wedding gift is sufficient. Here, gifts are small. Less like packages, more like postcards. Where the real magic lives in the act of giving itself.

And so I set off into the weather as well. The drizzle stiffened into rain as I walked, and I struggled to find my way through the labyrinthian urban outskirts of Tokushima. By the time I crossed the threshold into the Temple 1 complex, the rain had evolved into a downpour. While I hadn’t expected cheering crowds at the finish line, it was difficult not to feel let down by the chaotic ambivalence inside. Small packs of people dashed from station to station under umbrellas and ponchos. The stamp office was clogged with wet tourists.

An awning provided shelter to sit and observe, and I scanned the temple grounds. Whose white garments had seen over a thousand kilometers of Shikoku, and which sashes had just left the temple office? Whose hands bore dark tans? Which pant cuffs were frayed? I was searching for a physical manifestation of my accomplishment. Someone who understood where I came from, and could help me figure out where to go next. But this temple helped people leave, not return.

It was too wet to journal. I was glad, because I had nothing to record. I sat empty, as if I’d cried for an hour, though I hadn’t shed a tear. I made my way to the temple office, where I received a free stamp signifying I had completed the circuit. I gave my last care package to a pilgrim couple setting out to do the first twenty temples. A cashier noticed and brought me a matcha tea. I warmed my damp hands on the hot ceramic cup.

In a few minutes, my host for the night, Nishimura Makoto, met me at the Temple, remarked how skinny I looked, and drove to the nearest grocery store to prepare a celebratory feast.

In the summers, wealthy clients travel from all over Japan for Makoto’s sun detox program, where he buries people up to their heads in sand on the nearby beach for eight hours at a time. A reporter for a Japanese newspaper interviewed him while I washed my pilgrim garb. I bathed for the first time in days and reflected on how strange it was to be in the same place as I had been six weeks ago. I felt incredibly different, but in a way I couldn’t explain. I was happy that Makoto’s personality, combined with his limited English, meant I could keep the embarrassing secret to myself a bit longer. Over dinner, we listened to music and he told me stories about the underground blues movement in Japan in the 70’s. Makoto has never walked the circuit, but he seems to understand how I’ve changed since we first met. We played guitars to Mike Bloomfield vinyl sets early into the morning.

————————————————

ii. the day after

The next morning I’m on a steep funicular lifting me from Tokushima’s street level to the soaring highway above. The road connects Shikoku to Honshu; it will soon take me off this island. As I ascend, I watch Makoto bid me farewell from Shikoku. He waves, first with his left hand, and then with both hands, side to side above his head. Then, joyfully, it takes over his entire body. I’ve never seen anyone wave like this; it’s ridiculous, and delightful. I’ve only met this man twice, but cannot imagine the journey or the departure without him. I’m surprised to find that tears are streaming down my face.

The funicular doors open automatically and I’m relieved to not have to walk along another chaotic highway. My bus careens to a stop, and I shuffle into the front seat. The scenery catapults through the larger-than-life window. I’ve spent over six weeks of my life walking around this island. Would it take only days to drive? Hours? I’d wrung out so much meaning from slowing down, it’s hard to tell which version of Shikoku is closer to reality.

My final stop is Mt. Koya, or Koyasan, as it’s known. It’s one of the most sacred places in Japan, and the final resting place of the Shikoku pilgrimage’s prophet, Kobo Daishi. Henro traditionally visit Koyasan to pay their respects. The journey is a crash course reintroduction to crowded and touristy Japanese public transportation. I’ll travel 220 kilometers in over 6 hours instead of 6 days on foot.

——————–

Soon I arrive in Osaka, Japan’s third largest city. As I wade through the busy train terminal, I follow enormous laminated signs leading to a long line for the “Ultimate Koyasan UNESCO World Heritage Pass ®.” I don’t want to belong in this line, but I have no sedge hat, no pilgrim vestments: I’m just a tourist again, buying a tourist pass.

There is no worse charge than to be labelled a “tourist.” Being a tourist means – at best – to merely witness something deemed important by others. More often, it’s someone who takes and obscures something of beauty and importance. While tourists can’t hope to have an authentic experience, a traveler might. Or a vagabond. Is a pilgrim somehow different, or any better?

The act of pilgrim-ing changes the experience for all those who come after. On Shikoku, successive generations of Henro have streamed into a valley originally carved by Kobo Daishi. Over time its walls have deepened in tradition and broadened in accessibility. Henro have created new signs and guesthouses. Bicycles and tour-buses whisk them around the island on weekend-sized jaunts. They’ve shared their stories, and changed the very composition of future Henro.

Pilgrims, like tourists, come to do something that someone before them designated important. But unlike tourists, pilgrims relish those who came first. They don’t seek originality in their path. The fact that it is well worn means it’s fertile grounds for the sacred experience within. Part of what makes a Henro a Henro is to travel to honor Kobo Daishi. And so, l go. And remind myself that the throngs of people buying tacky tour-bus packages and carrying UNESCO passes long are pilgrims in their own right. Likely on more difficult journeys than I.

——-

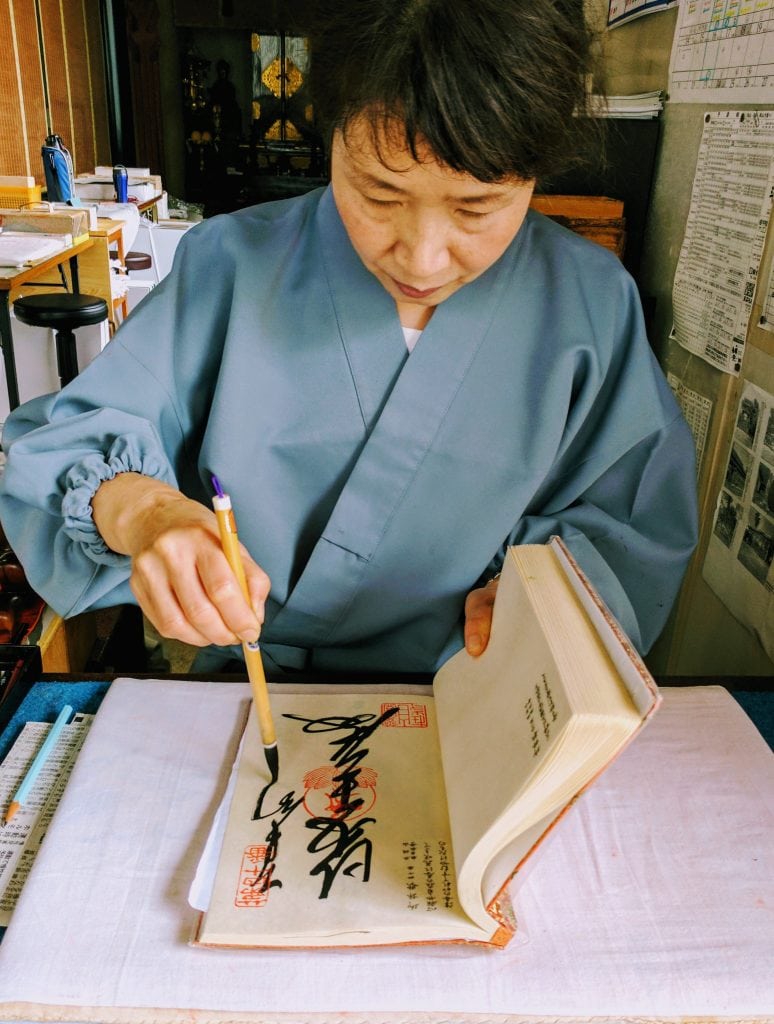

Koyasan has the density and feel of a small mountain resort town, but instead of hurtling down ski slopes and apres-skiing in hot tubs, there’s heart sutra calligraphy lessons and a forest of 200,000 ancient tombs. The town is compact. One long street services over 50 temples and the funicular station is accessible by public buses only. The dense forest where the Okunoin cemetery begins has been carefully curated for twelve hundred years and is revered across Japan. Thousand year old cedars tower over twisting paths representing centuries of funeral plots. The serpentine trails weave amidst a canopy of trees so tall and thick that even during the day the pathway lights remain illuminated.

I set out towards Okunoin temple, the final resting place of Kobo Daishi, at dusk. A final calligraphy stamp awaits me at the temple, if I can get there in time. Heading into mist slowly descending from the mountaintop, I notice that my feet no longer hurt from walking, but my worn soles make walking on the damp stones treacherous. A bridge spans a large gully separating the cemetery from the place Kobo Daishi sits in eternal meditation. As I approach, a monk seals the gate before I can cross; I’ve arrived minutes too late.

I have no choice but to walk 45 minutes through the cemetery into town. I weave deeper through the forest, lost, lost in thought, and conclusionless. Signposts are obscured by dark moss which also covers the gravestones and consumes anything near the ground. Gradually, one path splits into three, and then five, winding up and down the mountainside from the temple. The silence is as thick as the air. Every breath feels heavy with the significance of this mountain. The towering cedars are living guardians of the dead.

I’ll spend the next 18 hours in Koyasan biding my time until the Okunoin temple stamp office opens. Once it does, a monk gives me my final calligraphy strokes without fanfare or interest. I half-heartedly walk through several large temple complexes. I join morning meditation and chanting before dawn. The entire town is vegetarian, and there are three famous preparations of tofu. At my third tofu lunch of the day, my journal remains open to the same blank entry I started at Temple 1. I dread my imminent return to the real world. It’s not what I want, but it’s what I’m given; the meaning will have to unfold on its own time.

—————————

iii. epilogue

Six weeks is an unfathomably long time to do any one thing, let alone take a vacation, and most certainly to just walk around by yourself. It was frustrating and scary to think that what I’d just spent my precious sabbatical doing – what I suffered through – wouldn’t come with any measure of instant gratification or enlightenment. Koyasan was the beginning of these feelings of expectant emptiness. It was also the epicenter of Shingon Buddhism, the terminus of the pilgrimage, and the last days I’d have alone before tossing myself back into the jaws of Reality.

BUT, what I’ve begun to realize, months after finishing the pilgrimage, is that the experience was a glorious mystery which has steadily revealed itself over time. Though there were no big lessons learned, or truths uncovered during my anxiety-laden pacing about Koyasan, I can at least take a snapshot of what things look like from where I am now. It is, of course, subject to change. I’ll try to keep it short here, but please reach out if you want more detail:

-

Greater perspective and objectivity

Being handcuffed to myself for six weeks in Shikoku, with no witnesses and no escape, doing something physically and mentally demanding, allowed me to experience myself independent of my job. While away, I was unsure if things were improving or failing spectacularly in my absence, while hamstrung to do anything about it regardless. In the end, of course, everything came together [2].

-

New skills through experiences

I’m a bit less anxious, a touch more patient, a smidge more generous, a lot happier every so often. I’m much more comfortable with fewer possessions and the idea of sleeping in public. I know that I can live a pretty happy life for four months with only the belongings in my backpack, but I also know that solitary life is a more selfish one than I want to live. I’m grateful to have been able to try on that life for a spell.

One of my biggest takeaways from Shikoku is the power of experiential lessons. Almost all of my learnings can undoubtedly be found in various books. But the pilgrimage provided some structure and a concrete goal with which to self-examine. The day to day often wasn’t pretty, but it was all a part of a time-tested recipe.

-

Clarity for the future

The spirit of generosity shown to me by other Henro, and the residents of Shikoku, inspired me to spend some time figuring out how to give more directly through my actions. My current plan is to give back by starting a non-profit for Henro [3], to get more involved in a US poverty research non-profit called LEO [4], and to do some more writing.

As the truths emerge from my time on the island, I have this recurring vision of myself as a horticulturalist in a zen garden, trimming and manicuring the slopes and contours of my experience. Making sense out of it through a balance of crafting what’s there now, and pruning in anticipation of what is to come. On occasion, something breaks loose from the bottom of the pond at the center of the garden – a memory, or realization – and floats to the surface. I glide out and collect it. I can plant it on the banks of the garden itself, and it immediately becomes part of the larger ecosystem. Below the surface, the pond continues to process and synthesize my experiences. When they’re ready, they rise up to be part of the mosaic of my understanding of the world. Very little of it makes sense until it’s part of the broader whole.

I don’t know much more about Buddhism or Kobo Daishi than when I started, even after the 176 heart sutra recitations at 88 temples; the Japanese signs eluded me. But I know much more about myself. I know what I’m physically capable of, mentally predisposed for, and emotionally tied to. I know that my mind wandered. My feet hardened and my heart softened. I ended where I started. And that’s right where I needed to be.

Thanks for reading along, expressing encouragement, and welcoming me back with such heartfelt enthusiasm. Onegaishimasu – please and thanks in advance – I’ll continue to need your help even more in the next phase. Stay tuned!

1 In his book, “A Sense of Direction,” Gideon Lewis-Kraus highlights the shapes that form popular pilgrimages.

2 This story has a good ending, which again, wouldn’t be revealed until months after the pilgrimage. How much energy could I save, how much joy can I have, if I’d just surrender to the present moment?

3 The goal of Henro.co is to enhance the pilgrimage experience for visitors and Shikoku residents. Hopefully it will be both a great gift, and a commitment device to keep the lessons of the pilgrimage close.

4 The Lab for Economic Opportunities (LEO)’s mission is to reduce poverty in the United States by evaluating the impact of programs aimed at reducing poverty and improving lives, and spurring change at the national level through policy and awareness.